Celebrating Canada's amazing contributions to space exploration

Did you know that Canadian feet were actually the first to touch down on the Moon during the Apollo 11 mission?

National Space Day is on the 2nd of May, and Canada has many excellent reasons to celebrate, due to the contributions of our science and technology over the years.

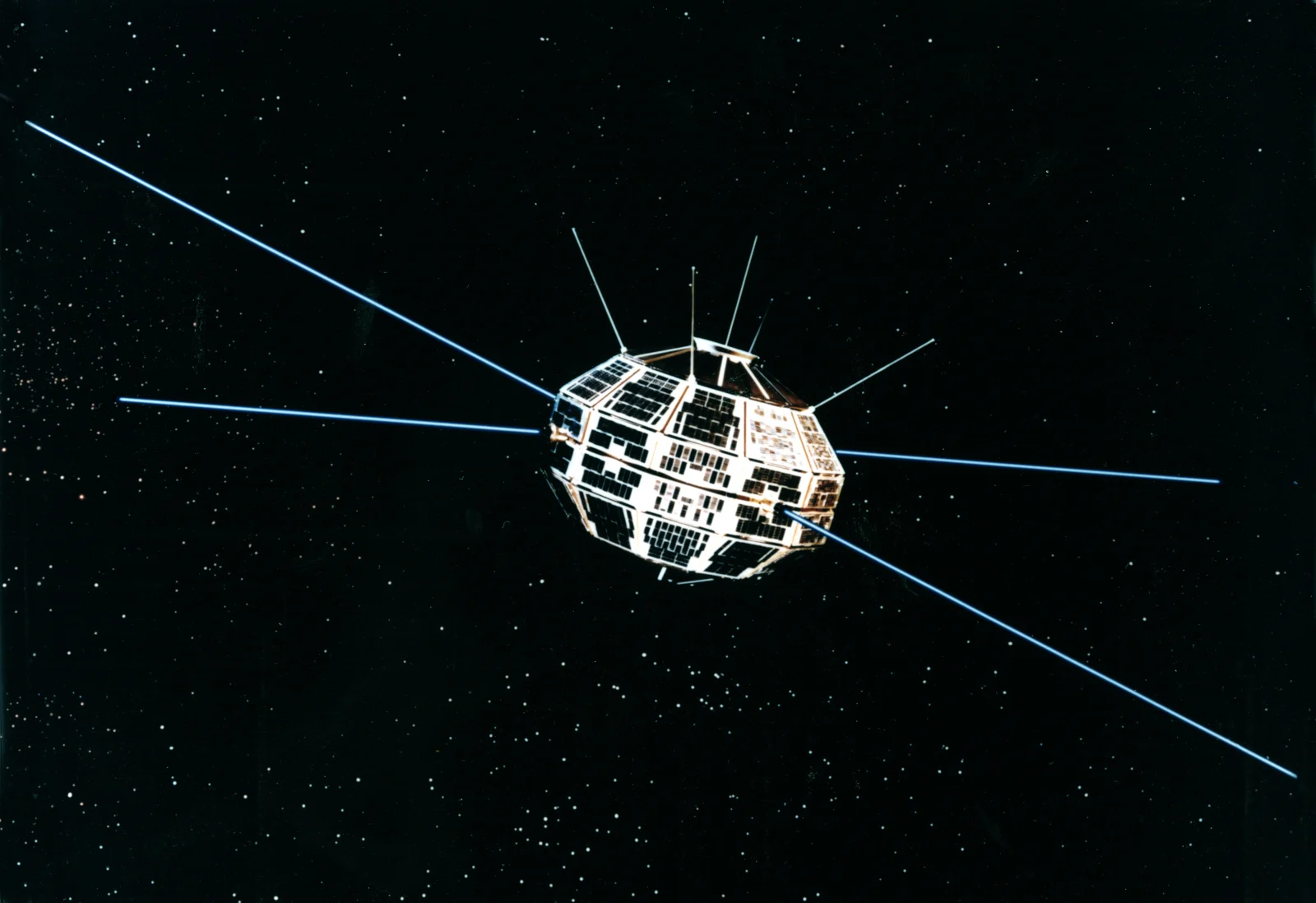

Third nation to build and launch its own satellite

The Soviet Union was the first nation on Earth to build and launch a satellite into orbit around our planet, with Sputnik in October 1957. The United States quickly followed behind with the Explorer 1 mission, in January of 1958.

On September 29, 1962, Alouette 1 launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in Californian, making Canada the third nation to build and launch its own satellite.

An artist's conception drawing of the Alouette 1 satellite in space. (Canadian Space Agency)

Flying at an altitude of 1,000 km, over twice the distance of the International Space Station's current orbit, Alouette 1 gathered data on Earth's ionosphere using radio transmissions between the satellite and the ground. It also detected high-energy particles from space, and it used antennae to measure radio noise that originated from our Sun and from the galaxy beyond our solar system.

Although Alouette 1 was only expected to last for around a year, it actually continued operating for a total of 10 years and one day, finally ending its mission on September 30, 1972.

This mission was followed by Alouette 2 in November of 1965, which would supplement Alouette 1 using a greater range of instruments. The ISIS 1 and ISIS 2 missions launched in 1969 and 1971, respectively, picking up from the Alouette program to study the upper ionosphere and take the first images of the Aurora Borealis from space.

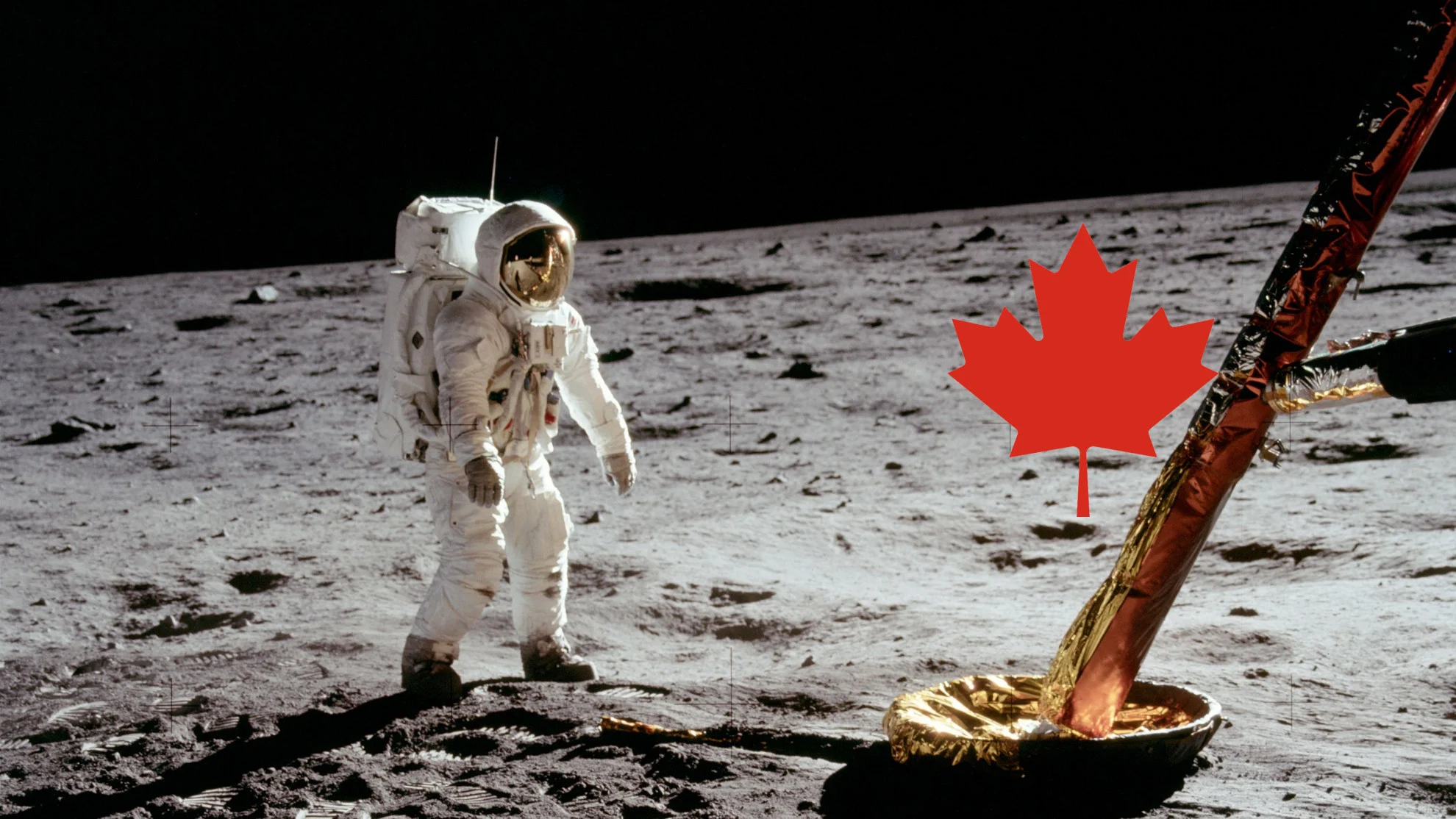

First feet on the Moon

Did you know that Canadian feet were actually the first to touch down on the Moon during the Apollo 11 mission?

At 10:56 p.m. EDT, on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong made history as the first human to set foot on another celestial body. At 11:15 p.m. EDT, Buzz Aldrin became the second to accomplish this feat.

Buzz Aldrin stands near one of the landing legs of the Eagle Lunar Module on July 20, 1969. (NASA)

However, over six hours prior to that, at 4:17 p.m. EDT, a set of Canadian feet touched down in the Sea of Tranquility first.

Although the Eagle Lunar Excursion Module was assembled, launched, and flown by Americans, the LEM's landing gear was manufactured by Héroux Aerospace of Longueuil, Quebec.

Those four landing legs still stand at Tranquility Base today. They were left behind with the rest of the descent stage when Eagle's ascent stage detached and propelled Armstrong and Aldrin back into lunar orbit to rendezvous with Michael Collins in the Columbia Command Module.

Buzz Aldrin stands next to the LEM in this photo taken by Neil Armstrong during the Apollo 11 mission on the Moon. (NASA)

DON'T MISS: Look up! What's going on in the May night sky?

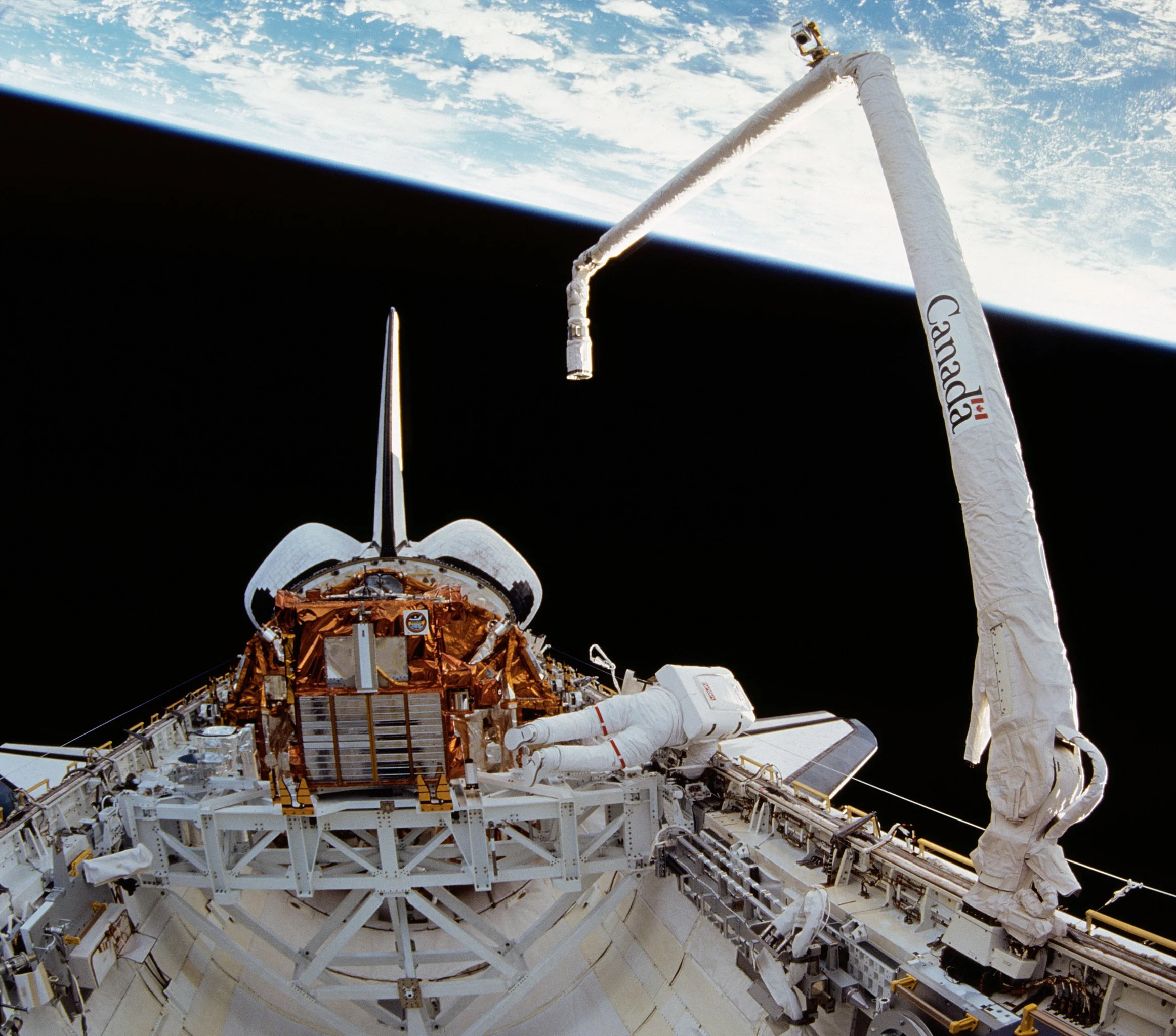

Three space robots (and one on the way)

When NASA launched the second of its Space Shuttle missions in November of 1981, Columbia was carrying a new space robot called the Shuttle Remote Manipulator System or SRMS. You likely know it by its more common name, though: the Canadarm.

Attached to the inside of the shuttle's cargo bay, Canadarm was designed to allow the astronauts inside the shuttle to manipulate science instruments, deploy equipment, and even release satellites into space.

The Canadarm is seen here, raised above the payload bay during the Space Shuttle Endeavour mission STS-72, on November 23, 2013. NASA astronaut Winston Scott can be seen near the base of the Canadarm while on a spacewalk. (NASA)

When the Space Shuttle Discovery blasted off in 1990, ferrying the Hubble Space Telescope to orbit, it was the Canadarm that gently transferred the telescope from the bay to its new home in space. On subsequent servicing missions, the Canadarm was used to grasp the telescope and bring it in, to give the astronauts access to its inner workings, and afterward it would again release Hubble to continue its remote exploration of the universe.

When the International Space Station was being built, Canada's contribution was the Canadarm2, which was delivered to the ISS in April of 2001. Canadarm2 was designed so either end of it could attach to the station in several locations. This effectively allowed it to 'walk', end over end, to wherever it was needed. The Mobile Base System was added in 2002, which gave Canadarm2 the ability to slide back and forth along the station's length. In 2008, the Special Purpose Dexterous Manipulator, or "Dextre", completed the system, expanding the capabilities of Canadarm2.

SpaceX's Dragon cargo resupply ship is caught by Canadarm2 on October 4, 2016, to be berthed to the International Space Station. (Credit: NASA)

These days, Canadarm2 and Dextre help maintain and repair the ISS, as well as assisting astronauts during spacewalks. Canadarm2 is also integral to the station's resupply program. Progress, Soyuz, and Crew Dragon spacecraft are capable of docking and undocking with the station all on their own.

However, Dragon 2 and Cygnus cargo ships must be captured by the arm and berthed to the station, and then unberthed and released by Canadarm2 at the end of their stay.

A computer model of Canadarm3 attached to the Lunar Gateway station. (Canadian Space Agency)

With NASA's plans to build the Lunar Gateway station, Canada has committed to provide a new Canadarm3 to help assemble and maintain that new lunar outpost.

Detecting snow and x-raying rocks on Mars!

When NASA landed their sixth successful mission on the surface of Mars, the Phoenix lander, it carried Canadian science on board.

Mounted on the lander's deck was a meteorological station, named MET. While MET's pressure sensor came from Finland and the wind monitor was from Denmark, the temperature sensors and lidar were supplied by Canada, with the entire instrument assembled and sent to NASA by the Canadian Space Agency. Previous missions, such as Viking 1 and 2, had carried weather instruments, but the lidar system was something new on the Red Planet.

According to the CSA: "By scanning and probing the Martian polar sky in such detail from the ground for the first time, Canadian researchers saw a variety of atmospheric activity in greater detail than ever before. They looked at ice and dust clouds, ground fog, and even saw dust devils across the landing site. Researchers are using this unique data from the red planet's polar region to create a clearer picture of how water cycles between surface ice and vapour in the atmosphere."

The Canadian weather station on the Mars Phoenix Lander is shown bottom centre on the lander's deck. Inset bottom right is a closeup of the Canada logo on the station's cover. Inset top left is the data from the weather station's lidar instrument, showing snow falling from high Martian clouds before it evaporates, thus they are labelled Fall Steaks (aka virga). (Main image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/Texas A&M University. Top left inset: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/Canadian Space Agency)

We think of Mars as a dry, desolate place, but one of the most remarkable discoveries from the Phoenix mission was that it snows there!

On September 3, 2008, the mission's 99th Martian day, the lidar picked up 'fall streaks' high in the sky above. Fall streaks typically go by another name here on Earth — virga. In this case, due to the temperatures recorded at the time, this would have been snowflakes falling from the thin Martian clouds, which then evaporated as they fell.

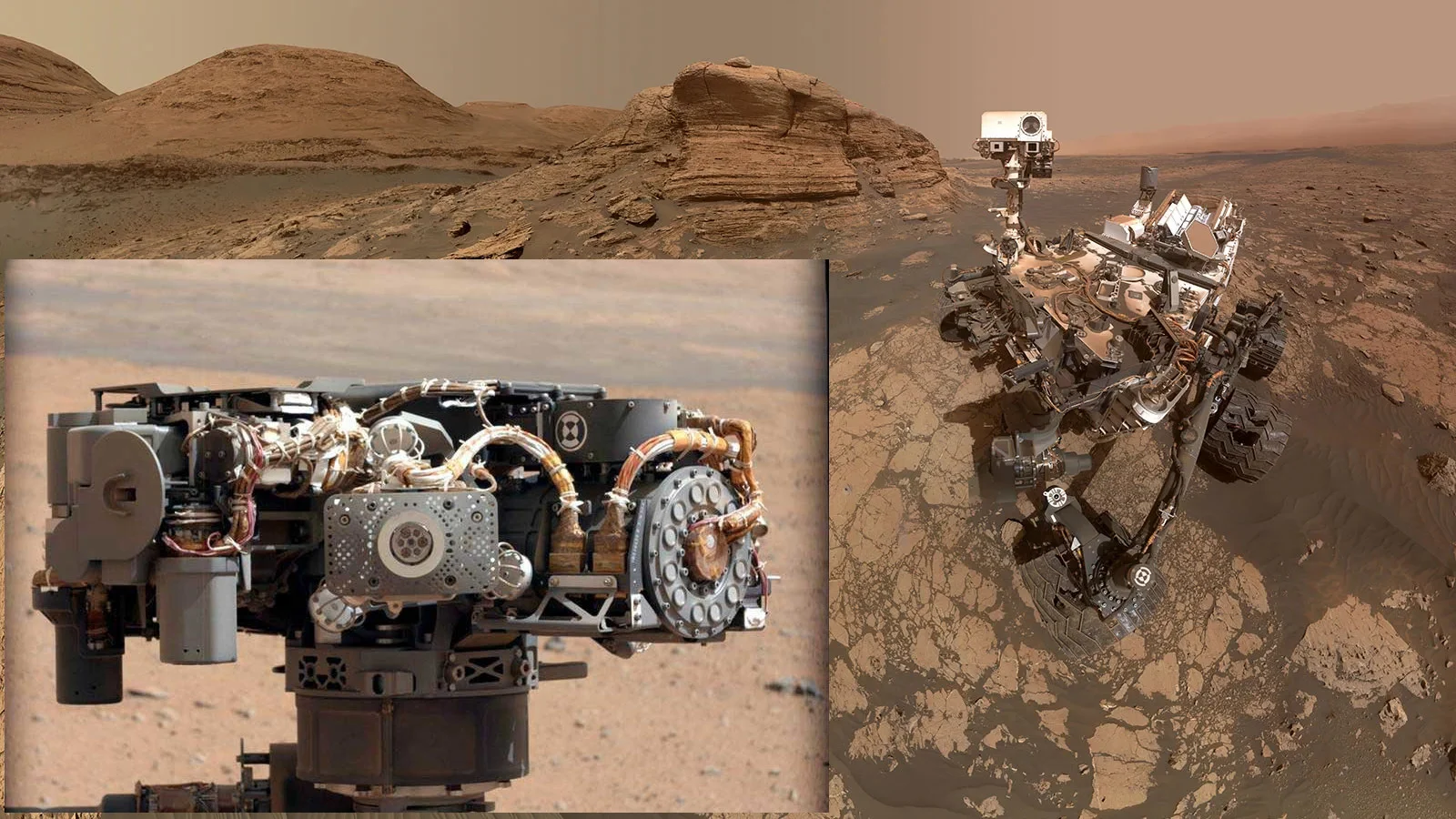

Nearly four years later, when NASA's Curiosity rover landed in Gale Crater on August 6, 2012, this one-ton science explorer carried another piece of Canadian science and technology — the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer, or APXS.

A selfie taken by the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity on March 16, 2021. Inset, bottom left, a closeup of the rover's science instrument "hand", centred on the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer, or APXS, taken on September 7, 2012. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

"Located on the end of the Curiosity rover's robotic arm, the sensor is placed close to a sample, which it bombards with X-rays and alpha particles (charged helium nuclei) to study the properties of the energy emitted from the sample in response," the CSA says. "The instrument takes two to three hours to fully analyze a sample and identify the elements it is made of, including trace elements. A quick-look analysis can be completed in about 10 minutes."

One of the most intriguing targets investigated by APXS is a rock Curiosity drove over in 2024. When the rock cracked apart, the rover cameras saw that it was entirely composed of strange yellow crystals. APXS revealed that it was elemental sulfur.

These yellow crystals were revealed after Curiosity happened to drive over this rock and crack it open on May 30, 2024. APXS revealed these crystals to be elemental sulfur. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

This is the first time this kind of sulfur has been found on the Red Planet.

"Elemental sulfur consists only of pure sulfur atoms, unlike the sulfur bound to oxygen in sulfate," says NASA, who noted that the region that Curiosity was in at the time was found to have rocks that are rich in sulfates. "It’s an odorless mineral that on Earth is created by a variety of different geological processes, including volcanic and hydrothermal activity. Curiosity’s team doesn’t yet know which processes would have formed the elemental sulfur found by the rover, but they’re searching for clues in the rocks and surrounding area."

Laser-mapping an asteroid

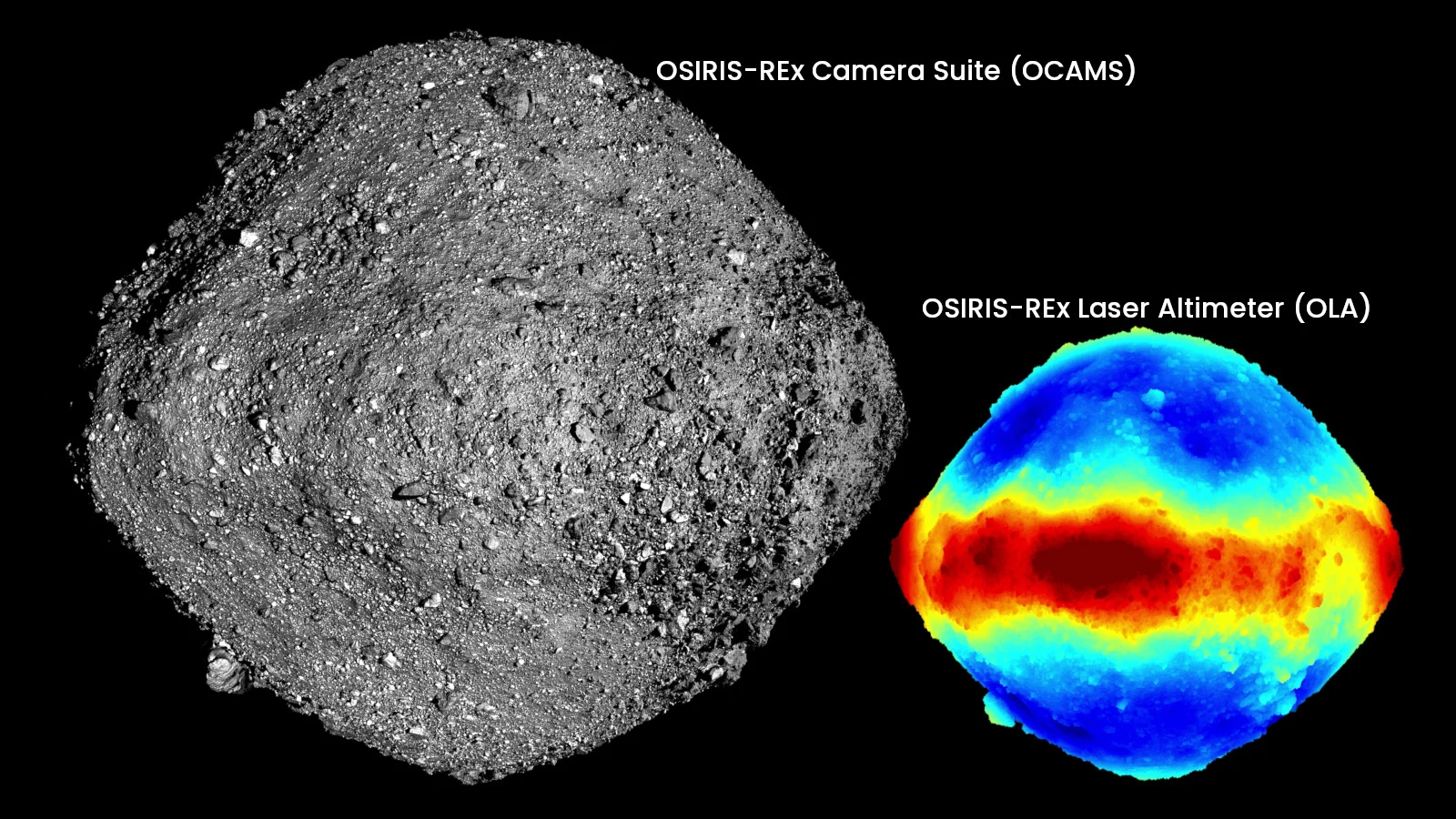

NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission blasted off in 2016, bound for near-Earth asteroid Bennu. On board the spacecraft was an instrument known as OLA — the OSIRIS-REx Laser Altimeter, a piece of Canadian technology that used a low-powered laser to map out the entire surface of the asteroid in 3D.

A view of asteroid Bennu taken by OSIRIS-REx's optical cameras, with the same view taken by Canada's OLA instrument showing the variations in terrain on the asteroid's surface, from lowest (dark blue) to highest (dark red). (NASA/CSA)

This map, along with concentrated scans of very specific regions of Bennu, would be crucial during OSIRIS-REx's most challenging and dangerous maneuver — touching the surface of the asteroid and blasting off a sample for collection.

READ MORE: Surprisingly salty asteroid Bennu contains the building blocks of life

Viewing the cosmos with Webb

The James Webb Space Telescope has been scanning the depths of the universe, helping us to unlock its secrets, while wowing us with absolutely incredible imagery.

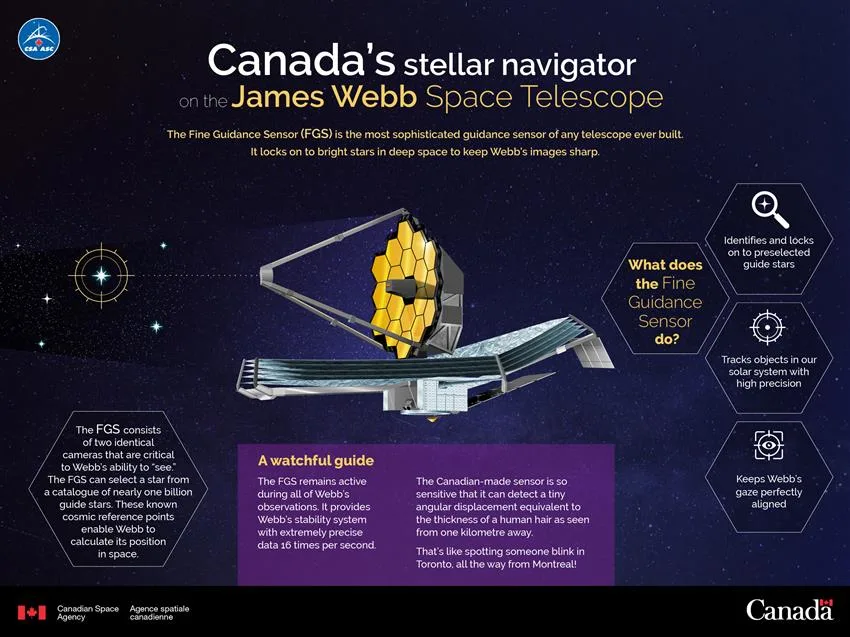

Canadian technology is a big part of why Webb's images are so good, thanks to two different instruments installed on board the telescope — the Fine Guidance Sensor and the Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS).

(Canadian Space Agency)

The Fine Guidance Sensor is what Webb uses to precisely determine its own location in space, locate its targets out in the cosmos, and stay steadily locked on to those targets, no matter their distance or any movement by the telescope or the subject from which it is collecting light. In other words, without the FGS, Webb simply couldn’t do its job.

(Canadian Space Agency)

NIRISS is an instrument focused on collecting light in the red to near-infrared part of the spectrum. It is capable of targetting its observations so closely that it can detect the presence of an alien exoplanet around a distant star. It can also split the light from that star and planet into its component parts, to analyze for the chemical composition of the exoplanet's atmosphere.

NIRISS's capabilities regarding alien worlds has earned it the nickname Canada's exoplanet specialist.

The Canadian astronaut corps

Last, but definitely not least, are the amazing people we have sent to space over the years.

The first Canadian astronauts were chosen in 1983, and the class consisted of Roberta Bondar, Marc Garneau, Steve MacLean, Ken Money, Robert Thirsk, and Bjarni Tryggvason. In 1992, four more joined the corps — Chris Hadfield, Michael McKay, Julie Payette, and Dave Williams. Jeremy Hansen and David Saint-Jacques were selected in 2009, and our newest astronauts, Joshua Kutryk and Jenni Gibbon, were chosen in 2017.

All 14 Canadian astronauts, past and present. Top left - Ken Money, Marc Garneau, Steve MacLean, Bjarni Tryggvason, Robert Thirsk, and Roberta Bondar. Top right - Chris Hadfield, Dave Williams, Michael McKay, and Julie Payette. Bottom left - Jeremy Hansen and David Saint-Jacques. Bottom right - Joshua Kutryk and Jenni Gibbons. (Canadian Space Agency)

Canadian astronaut milestones:

1984 — Marc Garneau is the first Canadian astronaut in space

1992 — Roberta Bondar flies on the Space Shuttle Discovery, becoming the first Canadian woman in space

1995 — Chris Hadfield is Canada’s first Mission Specialist on the Space Shuttle Atlantis and is the only non-Russian to visit the Mir space station

1999 — Julie Payette is Canada's first astronaut on the ISS

2001 — Chris Hadfield becomes the first Canadian astronaut to perform a spacewalk

2006 — Steve MacLean is the first Canadian to operate the Canadarm2, taking a handoff of equipment from the Canadarm on the Space Shuttle Atlantis

2007 — Dave Williams sets a record for longest Canadian spacewalk time, at 17 hours and 47 minutes over three EVAs

2009 — Robert Thirsk takes part in Canada’s first long-duration mission, spending six months on the International Space Station

2013 — Chris Hadfield becomes the first Canadian Commander of the ISS

2019 — David Saint-Jacques sets a record for the longest time in space for a Canadian, at 204 days

CSA astronaut Dave Williams is pictured here on a spacewalk during the STS-118 mission on August 11, 2007. (NASA/CSA)

For the future of Canadians in space, Jeremy Hansen was chosen in 2023 to be part of NASA's Artemis II mission. This flight, on board an Orion spacecraft, is currently scheduled to fly around the Moon and back, no sooner than April of 2026.

Jenni Gibbons was chosen as Hansen's backup for the mission, meaning that she will take over if Hansen is unable to make the flight for any reason. Gibbons is also in training for the position of lunar capcom, which is the human bridge between the astronauts and Mission Control, relaying commands and acting as support for the team in space. She will become the first Canadian to ever perform this task.

Although there have been significant delays to the launch of Boeing's Starliner-1 mission to the International Space Station, Joshua Kutryk is currently assigned to that flight. When he reaches the ISS, he will be Canada's eighth astronaut to fly on board the orbital science laboratory.