Failed Venus probe likely crashed to Earth early Saturday morning

Launched over 50 years ago, this piece of the Kosmos 482 mission was designed to survive the punishing conditions on Venus.

A piece of Soviet hardware built to survive the burning, crushing environment of Venus crashed down to Earth sometime early Saturday morning, and, so far, no one has any idea where.

On March 27 and March 31, in 1972, the Soviet Union launched two new spacecraft bound for the planet Venus. The first, Venera 8, became the second spacecraft to successfully land on our sister planet and send back data on its extreme environment. The other probably would have been named Venera 9 had it actually made the journey to Venus. However, a problem occurred after it reached space which trapped it in an elliptical orbit around Earth. The spacecraft was subsequently named Kosmos 482, instead, and it was left to eventually burn up in Earth's atmosphere.

The first pieces of Kosmos 482 reportedly came crashing down only a few days after launch, as four titanium spheres, each bigger than a basketball, landed in a farmer's field near Ashburton, New Zealand. There are reports that a similar object was found in 1978, about 20 kilometres away. Apparently, two other pieces reentered in the early 1980s.

However, what could be the final part has stayed in orbit since.

The Kosmos 482 descent module is likely an exact duplicate of this Venera 8 lander, which measures roughly a metre across and weighs about 500 kilograms. (NASA)

Now, over 53 years later, that remaining piece is expected to reenter Earth's atmosphere later this week.

Normally, this wouldn't be a problem. Most spacecraft launched into orbit are not designed to survive reentry. As they plunge into the upper atmosphere, travelling at speeds of around 25,000 km/h, they burn up and — at least in most cases — nothing reaches the ground intact.

However, this piece of Kosmos 482 is not like most other spacecraft. It was built to survive a trip down through the dense, scorching atmosphere of Venus.

An artist's impression of Venusian mountains, depicted for NASA's DAVINCI mission (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry and Imaging). (NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab)

With temperatures close to 500 degrees Celsius and air pressure 90 times what we experience here on Earth, landing on Venus is like being in an oven set at twice its maximum temperature, nearly a kilometre down in the crushing depths of the ocean.

"As this is a lander that was designed to survive passage through the Venus atmosphere, it is possible that it will survive reentry through the Earth atmosphere intact, and impact intact," Marco Langbroek, an expert on Space Situational Awareness at Delft Technical University in the Netherlands, wrote in his satellite tracking blog SatTrackCam Leiden.

"It likely will be a hard impact," Langbroek added, explaining that it is doubtful that the lander's parachute would deploy, given that it likely has dead batteries after 53 years in space. "There are many uncertain factors in whether the lander will survive reentry though, including that this will be a long shallow reentry trajectory, and the age of the object."

DON'T MISS: Look up! What's going on in the May night sky?

When did this happen? (Updated May 10!)

According to Langbroek, the final estimate for the reentry was between 1:09 a.m. EDT and 4:09 a.m. EDT on Saturday, May 10.

At 2:35 a.m. EDT, the ESA's Space Debris office reported that "The descent craft was seen by radar systems over Germany at approximately 04:30 UTC and 06:04 UTC, corresponding to 06:30 CEST and 08:04 CEST, respectively." Those times correspond to 12:30 a.m. EDT and 2:04 a.m. EDT, respectively.

Then, at 3:56 a.m. EDT, they updated this by saying "As the descent craft was not spotted by radar over Germany at the expected 07:32 UTC / 09:32 CEST pass, it is most likely that the reentry has already occurred."

Thus, the reentry ocurred sometime between 2:04 a.m. EDT and 3:32 a.m. EDT.

To represent the upcoming crash of the Kosmos 482 Venus lander, a NASA image of the Soviet Venera 8 descent stage has been digitally added to an artist's impression of an ESA Cluster mission satellite burning up as it enters Earth's atmosphere, using the GNU Image Manipulation Program. (NASA/ESA (CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)/Scott Sutherland)

When the Kosmos 482 lander came down, it would surely have produced a fiery display in the sky for anyone who happened to be in the area.

Although the probe hit the top of the atmosphere travelling at more than 25,000 km/h, based on Langbroek's calculations, he estimated that it would slow to around 242 km/h by the time it hit the ground.

Were it to have successfully landed on Venus in 1972, this object would have done so by first slowing down using the atmosphere, and then deploying a parachute for the final descent to the surface. It was not designed to survive a full-on impact at top speed, however its titanium shell makes it very tough.

Crash zone

As for where the Kosmos 482 lander crashed, this is hard to know for sure. They have narrowed it down, at least.

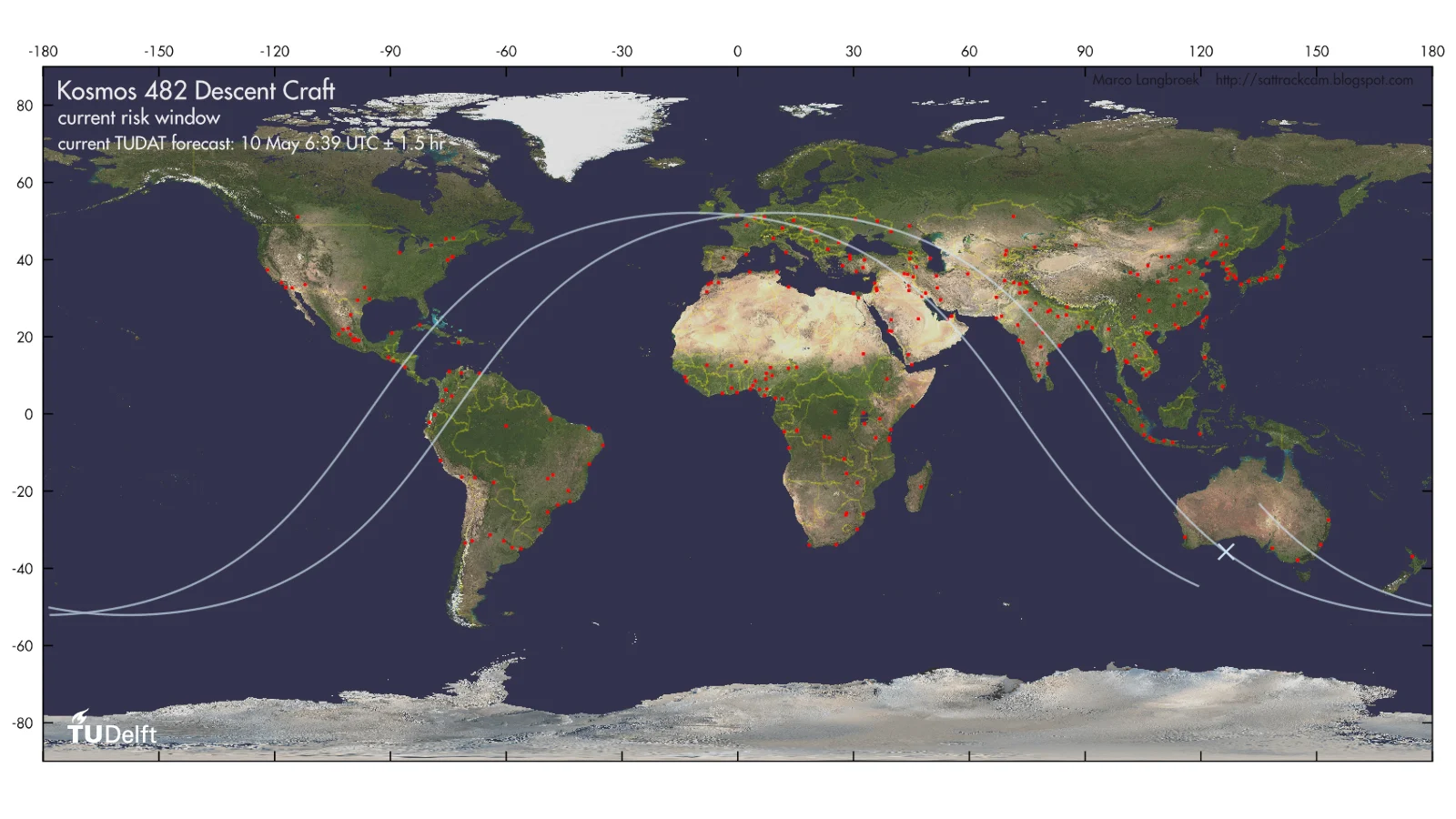

As of Saturday morning, Langbroek posted the following map, showing the last possible ground tracks for Kosmos 482 during its reentry.

The possible ground tracks of the Kosmos 482 Venus lander during the reentry window between 1:09 a.m. EDT and 4:09 a.m. EDT on Saturday, May 10. The blue X south of Western Australia represents the mid-point of this window, although not necessarily the most likely impact site. (Marco Langbroek/SatTrackCam Leiden (b)log)

There is more water than land along these remaining tracks. Thus, it is more likely that the probe splashed down into the ocean somewhere. However, there is still a chance it reentered somewhere over land.

No reports or video footage have yet surfaced, though.

Dangers from impact?

Given that we inhabit less than 15 per cent of Earth's surface, it was always highly unlikely that the Kosmos 482 probe would crash in a populated area.

However, in the case that it did, with a mass of around half a metric ton hitting the ground at 240 km/h, it would have certainly caused damage, and was also capable of causing injuries as well.

Given its rugged design, it would have probably crashed as one single object, Langbroek explained. So, rather than forming a strewn field of debris across a wide area, any damage it did cause would have been very localized, perhaps limited to a single building.

A hole in the ceiling is seen above a meteorite resting on a bed inside a B.C. home, in October 2021. The owner said she was sound asleep when she was awakened by her dog barking, the sound of a crash through her ceiling, and the feeling of debris on her face. (Submitted by Ruth Hamilton)

Unlike a meteorite, which would be very cold to the touch when it landed, this object could have been burning as it crashed. If so, it would have posed a fire hazard to anything around the crash site.

Fortunately, "this probe is inert and has no nuclear materials," says Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Also, the silver-zinc batteries used in Soviet spacecraft at the time are also considered to be non-toxic. Thus, there was no expected danger of chemical exposure, either.

Check back for updates.