Eyes up! The Northern Lights may put on an encore performance Tuesday night

The Northern Lights were a bit hit-and-miss on Monday night, so what happened there?

After a strong solar storm sparked dazzling aurora displays across parts of Europe and North America on Monday, there's a chance we could see another, more localized performance tonight.

We may not be seeing any auroras in the sky during the day, today, but Earth's geomagnetic field is still feeling the impacts of Monday's solar storm encounter.

According to NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center and NRCan's Canadian Space Weather Forecast Centre, we continue to have G2 to G3 level geomagnetic storms ("stormy" to "major storm" conditions via the CSWFC) throughout the day on Tuesday.

Space weather conditions from Jan 18, 19, and 20 are shown on the left, revealing the X-class solar flare on the 18th (top), the solar radiation storm that followed (middle), and the geomagnetic storms due to the CME arrival. On the right is the forecast, showing that G4 down to G1 storm levels are expected throughout the day on the 20th, then returning to substorm levels, with a brief return to G1 overnight into the 21st. (NOAA SWPC)

The geomagnetic storm conditions are currently forecast to ramp back down to substorm levels (below G1) later on Tuesday. However, given clear skies, parts of northern Europe and the east coast of North America could still catch some aurora activity after sunset.

Additionally, both the NOAA and NRCan forecasters give a chance of some Northern Lights being on display overnight into Wednesday. While SWPC has a brief return to G1 (minor) storm conditions, expected from around 10 p.m. to just after midnight, EST, the CSWFC forecasts a mix of stormy and major storm conditions across their auroral and sub-auroral regions.

The 6-hour and 24-hour forecasts for geomagnetic activity in the polar, auroral, and sub-auroral regions, covering January 20 and 21, 2026. (NRCan CSWFC/Scott Sutherland)

In all likelihood, this activity will be mainly confined to northern regions of eastern Canada, as well as across the central Prairies.

However, based on what has been happening over the past day, it would not be surprising to see some brief 'substorms' — bursts of stronger aurora activity that last for only a short time, and typically have limited extent, but can be quite spectacular to those lucky to spot them.

In Photos: Bright auroras light up the sky in Canada and around the world

So, what happened Monday night?

The past two days have seen some exceptional space weather activity.

First, an X-class flare exploded from sunspot region 4341 Sunday afternoon, dumping intense energy and light into space over a 7-hour period. Then, solar protons accelerated to fantastic speeds by the flare's energy bombarded Earth, producing a solar radiation storm that ramped up to severe levels over the next 24 hours. Following that, on hour 25 since the flare, the immense eruption that followed the flare — a 'halo' CME — impacted on Earth's geomagnetic field, immediately sparking a severe geomagnetic storm.

The bright solar flare from Jan 18, captured by the Solar Dynamics Observatory (left), the coronal mass ejection that followed it, imaged by the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, with Venus, Mercury and Mars also caught in the field of view (centre), and solar radiation storm causing bright 'snow' to appear as energetic protons strike the coronagraph's light sensor (right). (NASA SDO, NASA ESA SOHO)

This appeared to be the 'perfect storm' for aurora chasers across Europe and North America.

The dense coronal mass ejection absorbed a large portion of the flare's energy as it expanded into space. It also arrived very quickly. While typical CMEs take around three to four days to reach us, this one crossed the 150 million kilometres between the Sun and Earth in just over one day and arrived hours ahead of when it was expected.

And the CME's initial impact was exactly what we wanted. The magnetic field carried by the cloud of particles immediately formed strong connections with Earth's geomagnetic field. This allowed solar particles to stream down into the atmosphere, sparking incredible displays of the Northern Lights across Europe and parts of North America.

This cropped view of Real Time Solar Wind measurements shows how the CME's initial shock included the magnetic field going negative, resulting in favourable conditions for auroras. However, shortly after, as the bulk of the CME arrived, the magnetic field flipped positive and stayed that way for several hours, cutting off those favourable conditions. (NOAA SWPC/Scott Sutherland)

However, as the bulk of the solar storm washed over Earth, everything changed. As shown above, even as the density, speed, and energy of the particles flowing past the spacecraft all shot up, the magnetic field direction suddenly flipped positive.

Just as pushing together the like ends of two bar magnets (negative to negative, or positive to positive) causes them to repel each other, these conditions caused Earth's geomagnetic field to repel the CME, diverting much of it around us. This dampened down the geomagnetic storm levels, reducing them from G4 to G3/G2, causing the auroras to mostly retreat north for several hours, with the occasional substorm pulse during that time.

It was only when the magnetic field eventually flipped back to negative that more pathways opened in the geomagnetic field, causing geomagnetic activity to ramp up again, and for the auroras to surge to the south once more.

The challenges of Space Weather forecasting

This event reveals one of the limiting factors for space weather forecasting.

As a CME erupts, just by watching via satellite imagery, scientists can get a pretty good idea of its direction of travel, speed, density, and even the amount of energy it may have absorbed from the flare that spawned it.

The Jan 18 coronal mass ejection, imaged two hours apart by the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory's coronagraph instrument. The Sun is covered by a disk at the centre of the field of view, to better capture the fainter activity around it, as well as planets and stars in the view. (NASA ESA SOHO)

This allows them to model its progress between the Sun and Earth, days in advance, and provide us with an estimate of the level of geomagnetic storm the CME could cause, given ideal conditions.

One of those ideal conditions, though, is the direction of the magnetic field carried by the solar storm particles. Unfortunately, the only way we can know that is through direct measurement.

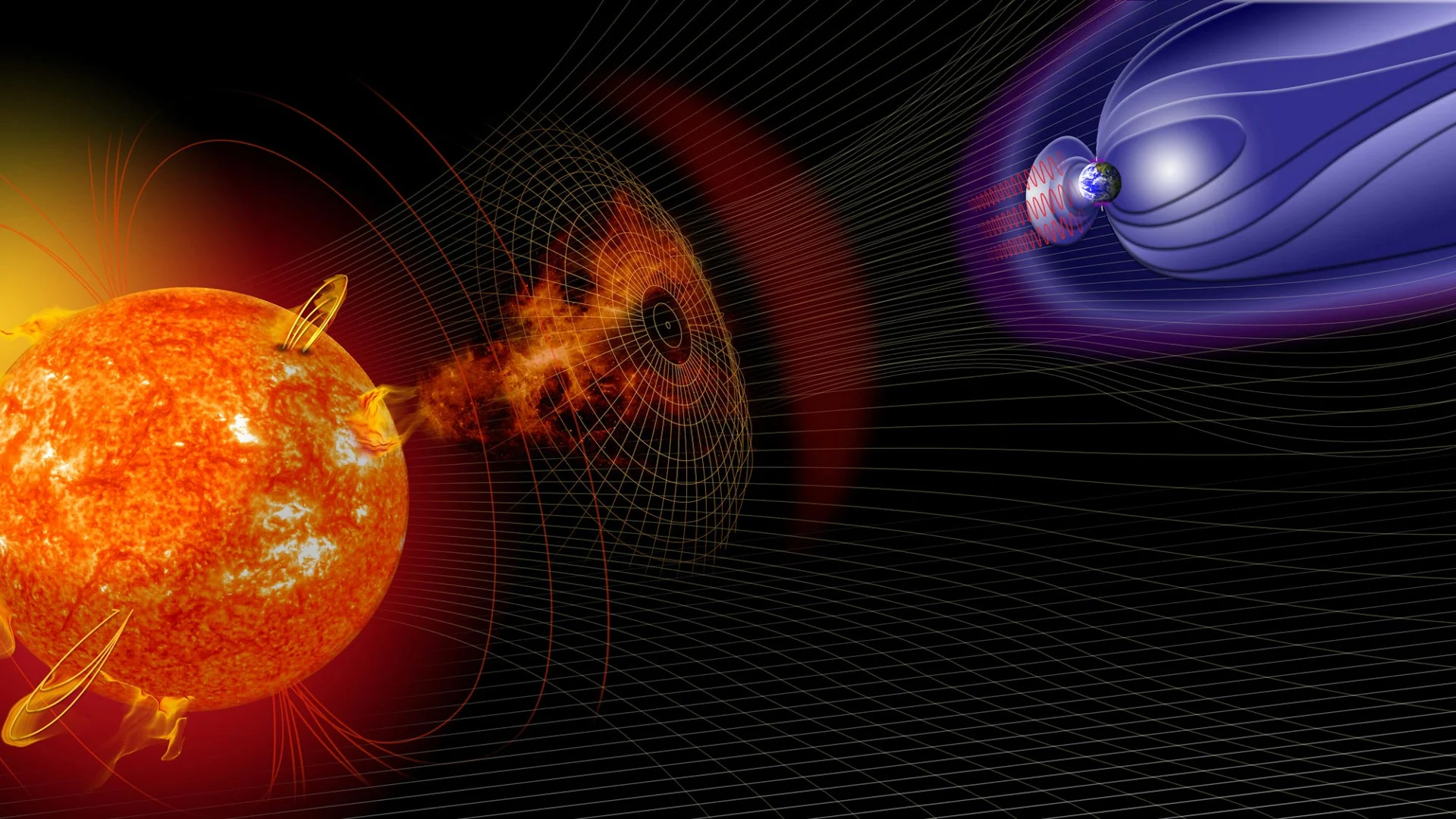

This artist's conception drawing shows a massive CME erupting towards Earth. At the exaggerated scale of the drawing, our farthest satellites that can directly measure that CME's magnetic field would be just to the left of Earth's magnetic field. (NASA)

Right now, we have two spacecraft — DSCOVR and ACE — that regularly provide those measurements. Given their relative proximity to Earth, though, we can't be sure about the full impact of a coronal mass ejection until it is nearly on top of us.

(Thumbnail image depicts vibrant ribbons of green and red auroras, captured by Jason Caine, from Lac La Biche, AB, on Nov. 12, 2025)