On this Summer Solstice, will you have one longest day or two?

All about the science and celebration of the Summer Solstice, plus, for this year, a unique oddity for parts of Canada!

Friday is the Summer Solstice for 2025, which is the typically longest day of the year for the northern hemisphere. But will you have two longest days?

As the Sun makes its daily passage through the sky, it's position changes in two different ways. The first is the most obvious, as it crosses from horizon to horizon, starting at sunrise and ending at sunset. The second way requires a bit more attention to notice, at least on a day-to-day basis. From here in the northern hemisphere, each day, starting in late December and ending in late June, the position of sunrise and sunset shifts northward along the horizon, and the Sun's path through the sky gets a little bit higher. Then, for the rest of the year, the trend reverses, with the position of sunrise and sunset shifting more southerly and the Sun's path getting lower in the sky.

At either end of this process, the Sun reaches a solstice — or solstitium in latin — which literally means 'Sun stoppage'.

This refers to how the Sun appears to stop or pause on these two days, reaching its most southerly sunrise and sunset, and its lowest path through the sky during the Winter Solstice, and reaching its most northerly sunrise and sunset, and its highest path through the sky during the Summer Solstice.

At exactly 2:42 UTC on June 21, we reach the summer solstice for 2025.

That translates to the following times across Canada:

12:12 a.m. on the 21st NDT,

11:42 p.m. on the 20th ADT,

10:42 p.m. on the 20th EDT,

9:42 p.m. on the 20th CDT,

8:42 p.m. on the 20th CST/MDT, and

7:42 p.m. on the 20th PDT.

This marks the start of astronomical summer for the northern hemisphere for this year.

Tracking the Sun

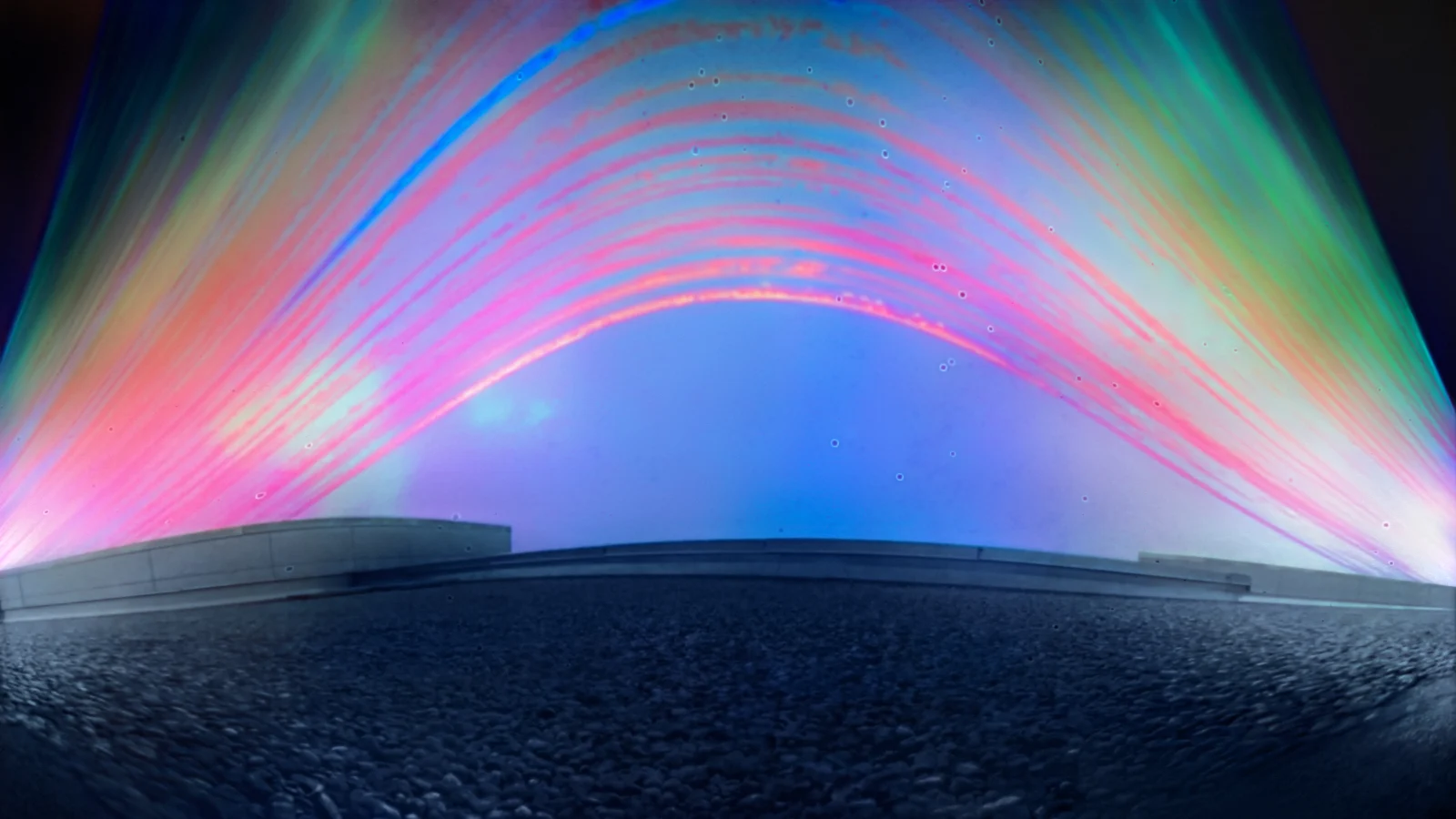

This one image, called a 'solargraph', captures the path of the Sun across the southern sky from June 20 through December 20, 2023. (Bret Culp, used with permission)

The image above is an example of solargraphy.

On June 20, 2023, award-winning photographer Bret Culp accompanied me up onto the roof of Weather Network headquarters, where we placed three small pinhole cameras, the inside of each lined with a piece of photographic paper. Leaving the cameras there for six months, we collected them on December 20, and Bret developed the resulting solargraphs. Above is one of the three images.

What we are seeing here is the path of the Sun, as it tracked from horizon to horizon, each day during those six months. The tracks closer to the top of the image are the first that were recorded, and the ones nearest the bottom were the last. Thus, with one image, he captured the motion of the Sun in the sky from the summer solstice through until the winter solstice.

Culp says that the breaks in any specific curve are caused by cloudy periods during that particular day.

"The colours are not direct depictions of the scene but a consequence of the paper's chemical reactions to extreme overexposure, the influence of uncontrollable factors such as moisture, dirt or fungus that may invade the camera, and excessive temperature fluctuations," Culp explains on his website. "Additionally, each brand of photography paper has a unique chemical makeup, resulting in different colour schemes."

What's behind this pattern?

Throughout human history, those that watched the sky noticed that year-by-year, the objects there — the Sun, Moon, and stars — would trace very specific, repeating paths.

Ancient monuments like Stonehenge, the temple of Karnak in Egypt, and Chichén Itzá in Mexico are just a few that were built to form specific alignments with these patterns in the sky. These locations still draw significant crowds as we transition between seasons — at the vernal and autumnal equinoxes, and the winter and summer solstices.

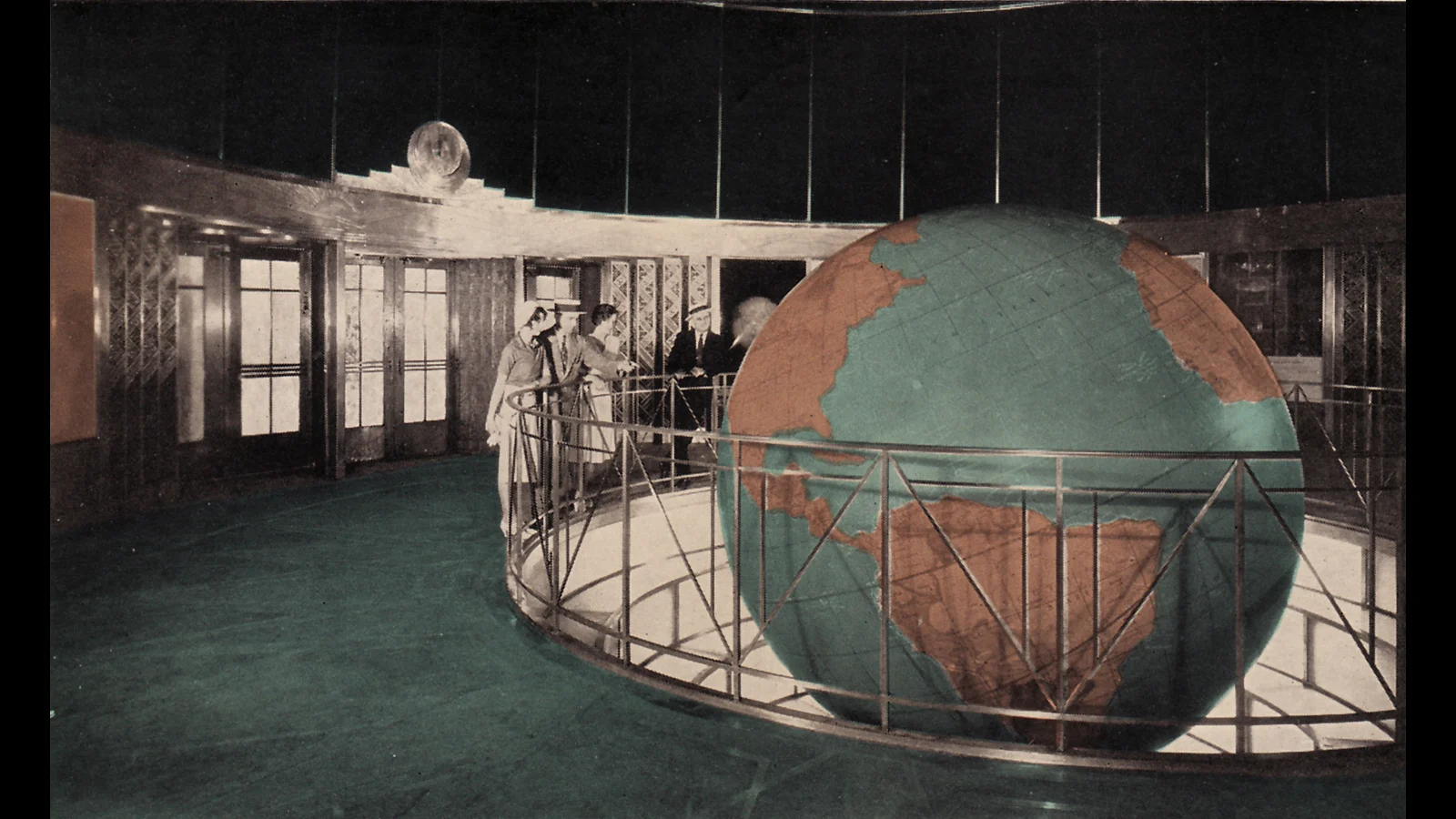

The best way to see the reason for this pattern is to look at how our planet orients with respect to the solar system and the Sun. You don't need to fly far out into space for this, fortunately. Just look at a globe.

The lobby of the Daily News Building in Manhattan, pictured in 1941, is shown in this colourized postcard. (Wikimedia Commons)

Globes are nearly always tilted to one side, and it is for more than aesthetic reasons. It reflects the 23.4° tilt of the Earth's axis compared to the path the planet traces around the Sun.

This tilt is the reason for our seasons.

Earth doesn't 'wobble' back and forth by 23.4 degrees throughout a year, though. Earth's tilt is relatively constant as we orbit the Sun, with the North Pole pointed towards the star Polaris. The day-to-day changes in the Sun's position in the sky are solely the result of how our view of the Sun changes as we orbit around it on our tilted planet.

As Earth goes through one full orbit of the Sun (as seen in the video above), the tilt causes the northern hemisphere to be pointed more towards the Sun during one half of the year. The southern hemisphere is pointed more towards the Sun for the other half of the year.

Take a location in Earth's northern hemisphere — Winnipeg, for example. During the summer, sunlight shines down on the ground there at a steep angle. So, each beam of sunlight delivers its energy to a relatively small area. In the winter months, though, the Sun's rays strike the surface at a more shallow angle. With the same amount of energy spread out over a larger area, it means less overall heating of the ground. It's this difference that makes the summer months hotter and the winter months colder.

The equinoxes — in March and September — mark the transitions between those two halves of the year, when the Sun is directly above the Earth's tilted equator. The solstices mark the points when the hemispheres reach their maximum angle — one towards the Sun and one away from the Sun — and the Earth's axis lines up perfectly with the axis of the Sun.

The longest day(s) of the year

The Sun is at its highest in the sky on the summer solstice. Essentially, it takes the longest path possible across the sky for whatever latitude you live at, and thus it is the longest 'day' of the year.

Something a little unusual is happening in 2025, though, at least for part of Canada.

Here, we will see the Sun at its highest in our sky during the day on June 20. However, the exact moment when Earth's axis lines up with the Sun's axis, and the Sun is at its absolute highest point in the sky relative to the entire planet, will occur when it is nighttime here. So, what happens then?

Well, for some, it means you don't have just one longest day. Instead, you have two!

The entire country will experience the longest day of the year on Friday the 20th.

However, if you live anywhere from northern and eastern Ontario to the Atlantic coast, Saturday the 21st will be the exact same length as the 20th, down to the second. This includes Timmins, North Bay, Ottawa, and Bainsville in Ontario, plus everywher to the east — all of Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

To be clear, though, the difference between the 20th and 21st for the rest of the country will be miniscule, with the 21st only 1 second shorter than the day before.

Exactly how long the day will be for your community depends on what latitude you live at. Those farther north will experience a longer day. Everyone north of the Arctic Circle, above 66 degrees latitude, will have 24 hours of daylight.

Day of celebrations

Every year on the summer solstice, Stonehenge, the ancient monument in Wiltshire, England, becomes crowded with people, all there to watch the Sun rise.

Whether they're actual practitioners of Druidry or just there for the spectacle, attendees are treated to a sunrise that will line up exactly over the 'Heel Stone', as viewed from the centre of the monument.

This image, screen-capped from Google Maps, shows the Stonehenge site, with an arrow indicating the alignment of the Sun on the morning of the June solstice. (Google/Scott Sutherland)

According to Frank Somers, from the Amesbury and Stonehenge Druids, celebrating the summer solstice at Stonehenge is about observing the cycles of nature.

"If you turn up at the changes between the seasons and observe that change," he told the International Business Times UK back in 2014, "you can become better attuned to those cycles in yourself, and you're a part of them."

In Sweden, the celebration of Midsummer, which occurs on June 20 this year, is one of the most important holidays of the year, on par with Christmas.

According to the website visitsweden.com: "The successful midsummer never-ending lunch party formula involves flowers in your hair, dancing around a pole, singing songs while drinking unsweetened, flavoured schnapps. And downing a whole load of pickled herring served with delightful new potatoes, chives and sour cream. All in all, a grand day out."

In Fairbanks, Alaska, residents usually mark the longest day of the year with the Midnight Sun Game.

While some baseball games are played as night games, the Midnight Sun Game has a whole different take on this concept. The first pitch of this game is thrown at 10 p.m. on the solstice, and the game typically lasts until 1:30 a.m. the next day. The big difference being, due to the amount of sunlight the area sees around the solstice, the Midnight Sun Game doesn't need a stadium with lights for the teams to play!

According to Explore Fairbanks: "The 'high noon at midnight' classic is played entirely without the use of artificial light. The Midnight Sun Game is a Fairbanks tradition that dates back to 1906 as a bar bet between the Eagle's Club and the California Bar, led by Eddie Stroecker, 'Father of the Midnight Sun Game.' Though the game is played through the hour of midnight, artificial lights are never used — and have never been used in the history of the event."

This year, in 2025, it is the 120th Midnight Sun Game, and on June 20, the Alaska Goldpanners will be playing against the Anchorage Glacier Pilots.

(Thumbnail credit Clive Ruggles/International Astronomical Union (CC BY 4.0). The image brightness and contrast have been adjusted from the original, darker picture, to make the standing stones of Stonehenge easier to see.)