Giant iceberg breaks from Antarctica, revealing mysterious underwater ecosystems

Little is known about life underneath Antarctica.

On January 13, 2025, iceberg A-84, which is roughly the size of Chicago, broke from the George VI Ice Shelf, a giant floating glacier attached to the Antarctic Peninsula ice sheet, leading to the discovery of new aquatic species and a healthy, untouched ecosystem.

On January 25, researchers specializing in several fields, including geology, physical oceanography, and biology visited the exposed seafloor left behind when the iceberg broke away. Coincidentally, they had been conducting research nearby but jumped on the opportunity to explore the newly-exposed area, representing an area of 510 square kilometres, which had previously been inaccessible to humans.

The MODIS Corrected Reflectance satellite imagery showing the iceberg calved from George VI Ice Shelf in the Bellingshausen Sea on 19 January 2025. (NASA Earth Science Data).

“We seized upon the moment, changed our expedition plan, and went for it so we could look at what was happening in the depths below,” expedition co-chief scientist Dr. Patricia Esquete of the Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies (CESAM) and the Department of Biology (DBio) at the University of Aveiro, Portugal says in a statement.

“We didn’t expect to find such a beautiful, thriving ecosystem. Based on the size of the animals, the communities we observed have been there for decades, maybe even hundreds of years.”

New species discovered

The Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) SuBastian, used to observe the seafloor for eight days.(Alex Ingle / Schmidt Ocean Institute)

Over eight days, the team used a remotely-operated vehicle to observe "flourishing ecosystems" on the seafloor, at depths up to 1300 metres.

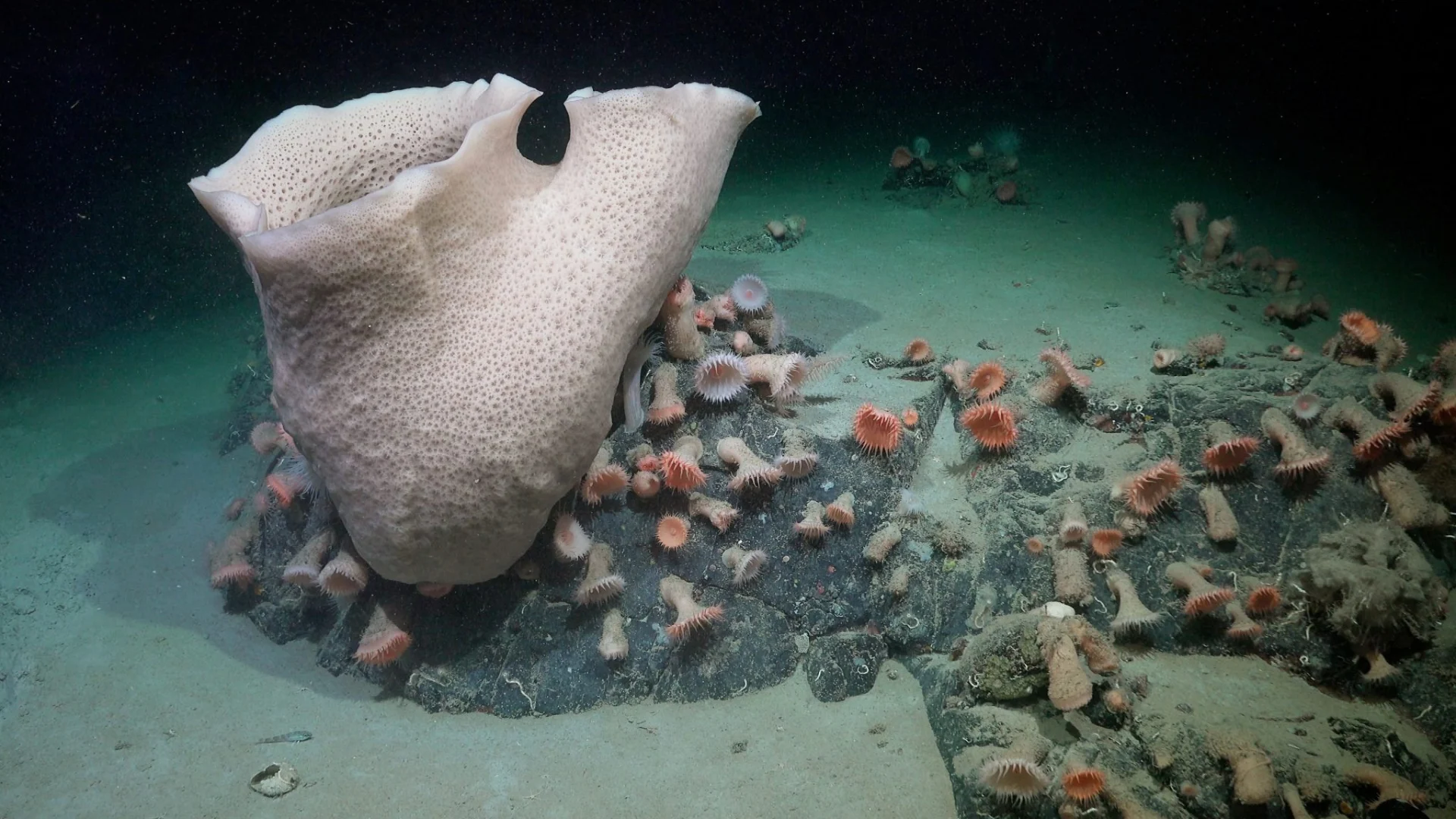

Coral, sea sponges, anemones, ice fish, and sea spiders are among some of the creatures found.

So far, the study has led to the discovery of at least six new species, but there may be more to come as additional specimens are analyzed.

The researchers say the findings offer greater insight into what exists below the Antarctic ice sheet.

A large sponge, a cluster of anemones, and other life is seen nearly 230 meters deep at an area of the seabed that was very recently covered by the George VI Ice Shelf, a floating glacier in Antarctica. Sponges can grow very slowly, sometimes less than two centimeters a year. Therefore, the size of this specimen suggests this community has been active for decades, perhaps even hundreds of years. (Caption and photo: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute)

Unclear how the ecosystems get nutrients

Many deep-sea ecosystems get nutrients from the surface, which slowly float to the bottom of the sea. But the newly-discovered ecosystem has been covered by a 150-meter-thick layer of ice for hundreds of years, blocking the flow of those surface-level nutrients.

The team suspects ocean currents may move nutrients below the ice, allowing for these underwater communities to grow. But as of now, the precise way the ecosystems sustain themselves remains unknown.

A helmet jellyfish drifts with tentacles splayed in the Bellingshausen Sea off Antarctica, an area in where the shelf break and slope are cut by several underwater gullies. (Caption and photo: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute)

“The science team was originally in this remote region to study the seafloor and ecosystem at the interface between ice and sea,” Schmidt Ocean Institute Executive Director Dr. Jyotika Virmani says.

“Being right there when this iceberg calved from the ice shelf presented a rare scientific opportunity. Serendipitous moments are part of the excitement of research at sea – they offer the chance to be the first to witness the untouched beauty of our world.”

Header image: A solitary hydroid drifts in currents approximately 380 meters deep at an area of the seabed that was very recently covered by the George VI Ice Shelf, a floating glacier in Antarctica. Solitary hydroids are related to corals, jellyfish, and anemones, but do not form colonies. (Caption and photo: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute)