Melting permafrost could unload billions of tonnes of carbon by 2100

A new study says billions of tonnes of defrosted carbon could end up getting released into the atmosphere by 2100 as a result of melting permafrost, further adding to the planet's warming from more greenhouse gases.

With Earth's global temperatures continuing to escalate, scientists are warning of the potential release of billions of tonnes of frozen carbon in the decades to come, thanks to melting permafrost.

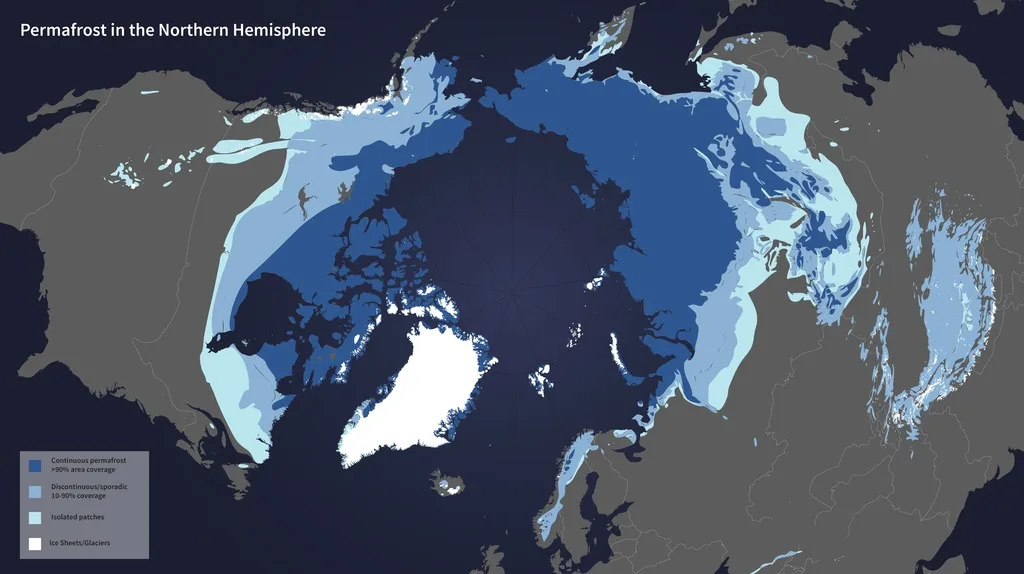

A new study indicates that between 119.3 billion tonnes and 251.6 billion tonnes of previously frozen carbon would be prone to microbial decomposition by the year 2100, thanks to enhanced warming in permafrost areas in the Northern Hemisphere.

SEE ALSO: Smaller ozone hole in 2024 pushes Earth closer to seeing it vanish

If it does get released, it will be discharged into the atmosphere and further increase the planet-warming greenhouse gases. Permafrost is a layer of soil, rock, and any other subsurface Earth material that exists at or below 0 C for two or more consecutive years.

While most of the newly thawed carbon should remain safely stored underground in the deep layers of soil in this century, four to eight per cent of it could decompose and release into the atmosphere. But it could still add an additional 0.1 C of warming by 2100.

(NASA)

"Our research underscores the significant threat that the substantial amount of newly thawed [carbon] poses to climate change mitigation efforts, particularly if any process accelerates the decomposition of organic [carbon] in deep soil layers," the study's authors said.

A fair amount of thawed carbon could be released

At conservative estimates, the study indicated a considerable amount of thawed carbon will be released. At four per cent of 119.3 billion tonnes of carbon, that would be an estimated 4.77 billion tonnes, and at eight per cent, that would be 9.54 billion tonnes, approximately.

When looking at the highest potential total of thawed carbon getting discharged, four per cent of 251.6 billion tonnes is approximately 10.1 billion tonnes of carbon, while eight per cent would be an estimated 20.1 billion tonnes.

However, as the study pointed out, there is a potential mitigating factor involved in how much could actually get released--the enhanced plant carbon digestion due to rising, atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels.

(Getty Images Plus/NicoElNino. Creative #: 1383854915)

The study, published in the journal, Earth’s Future, said permafrost soil houses vast amounts of organic carbon housed within it that is prone to global warming, and it may exacerbate climate change through greenhouse gas emission.

Flavio Lehner, chief climate scientist at Polar Bears International (PBI) and assistant professor at Cornell University, said the approximate amount of warming the planet has already incurred is sufficient enough to begin the process of permafrost thawing that's happening now.

"Generally, the more we warm, the faster ice melts [and] the faster permafrost thaws, as at its core," said Lehner, in an interview with The Weather Network earlier this year.

"This is like a simple physics exercise that relates to the temperature difference between two objects. If that temperature difference is large, then the exchange of heat between these two objects is faster because, fundamentally, they're just trying to equilibrate temperature, and that's exactly what's happening here, as well."

WATCH: Melting permafrost erased an entire Inuit village in Canada's North

Locales, short-term weather can 'complicate' the story

Lehner did say, however, there are certain factors that "complicate the story a little bit" in a specific location.

For example, you can temporarily have a rise of snowfall in a warmer climate, something scientists see in parts of the Arctic today, he added.

"If you do have more snowfall, and that sits on permafrost, it actually acts as an insulation. Not in terms of helping the permafrost stay frozen, but quite the opposite. Instead, it helps the permafrost melt, like thaw faster, because it insulates it from cold winter air," said Lehner.

Permafrost. (karenfoleyphotography/Getty Images-1421683611-170667a)

That aforementioned scenario has also been witnessed in the decomposition and release of the carbon in permafrost, which can "actually be accelerated" if there is increasing snowfall sitting on top of the permafrost during winter, Lehner said.

"If you do have permafrost thawing, the ground can collapse [and cause] sinkholes, [which] can massively disturb the ecosystem, and lead to more additional and abrupt thawing as you kind of expose more of the deeper layers of the ground to to the atmosphere above it," said Lehner.

"Taking these things together, there are some scientists that think the current projections of how fast permafrost might be thawing, [which] are largely based on climate model simulations, might even be a little bit on the conservative end because the climate models we're using today, they do not resolve all of the processes I just talked about very well."

Permafrost. (Michael Workman/Getty Images/1784183054-170667a)

Will all carbon stored in permafrost eventually be released due to warming?

Various estimates put the amount of carbon contained within permafrost in the Northern Hemisphere at anywhere from 1,400 gigatonnes to 1,7000 gigatonnes.

The Polar Bears International's chief climate scientist said humans emit about 40 gigatonnes of carbon per year currently, by comparison.

"In terms of the total carbon that [is] stored, [these amounts cited in the study] will be 40 times our current, annual emission. It's a huge amount of carbon. Now, obviously this wouldn't be released all at once, because the permafrost is dying, still relatively gradually, and it still takes time for the carbon to come out," said Lehner.

(-acilo-E+-Getty-Images)

With the amount of carbon that humans have emitted over the last 150 to 200 years, leading to our nearly 1.5 C of global warming, then all of the carbon that's currently stored in permafrost––if it was fully released––would probably result in another 1.5 C of warming, at least, Lehner said.

He noted the predicted carbon amounts in the study that could be released by 2100 would result in a much smaller warming increase, possibly generating a further 0.1 C increase.

"So [that] will be on top of the warming that comes from all the other greenhouse gas emissions that we're [putting in our atmosphere] in our industrial world, which we're thinking would currently lead to about 3 C of warming by the end of this century," said Lehner.

"[In] that sense, it's a small, additional fraction of warming that we're expecting this century from permafrost. Of course, looking further into the future beyond 2100, that contribution from permafrost might become relatively larger if we indeed continue to warm the planet."

Permafrost. (milehightraveler/Getty Images/982227048-170667a)

With human industrial activities ongoing and the globe continuing to warm, are we doomed to eventually release all of the carbon stored in permafrost?

"I think it's difficult to give an exact probability for this, as it really depends on what humans are doing in terms of their emissions in the industrial world," said Lehner. "The point here is that this is still very much dependent on how much we warm the planet entirely."

Lehner noted that "this is not something we think is a runaway [greenhouse] effect."

"We still have a lot of agency over what will happen here, and at the same time, that means it's difficult to give an exact probability of this occurring," said Lehner.

WATCH: Globe sees second-warmest March; Arctic sea ice hits new low

Thumbnail courtesy of daniloforcellini/Getty Images/1500911051-170667a.